Hey there friends, patrons, and fellow mythical astronomers! It’s your starry host, Lucifer means Lightbringer, back with a new series – the Weirwood Goddess. I wasn’t planning on making a new series, but it sort of just grew out of the Weirwood Compendium series as I was writing and researching. I started with a small section in a wWeirwood Compendium essay about Nissa Nissa’s overlap with the weirwoods, and it grew to a large section, then it’s own essay, and now it’s a whole series. We were long overdue for some gender equality and goddess worship, and the Weirwood Compendium research based on the ash tree has taken us here, and so I present to you what I think is one of the most important writings that I have done: Weirwood Goddess One, Venus of the Woods.

I want to get right to it, so let me quickly blow the herald’s trumpet in salute of our two new Guardian of the Galaxy Patrons: Lady Diana, the ghosts huntress, pursuer of truth and guardian of the King’s Crown, which is the Cradle north of the Wall; and our former House Cancer zodiac patron, Lady Jane of House Celtigar, the Emerald of the Evening and captain of the dread ship Eclipse Wind, who is now the guardian of the Crone’s Lantern. You can still claim any of the other on-zodiac constellations such as the Galley, the Horned Lord, the Ice Dragon, the Moonmaid, and a few others by clicking the Patreon link at the top of the page, and we will be eternally grateful for your support.

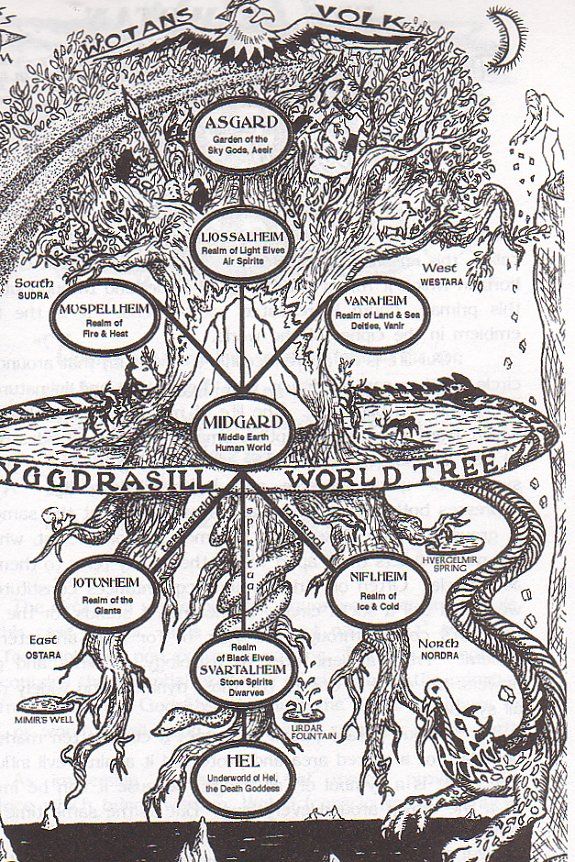

Alright. In the last episode, we saw that our friendly author Mr. George R. R. Martin appears to be using the symbolism of Yggdrasil as an ash tree to great effect, mostly pertaining to the idea of the weirwoods as a symbolic burning tree which enables transcendence of death. We talked about the location of the meteor impact as a kind of ground zero for Lightbringer’s forging and Azor Ahai’s rebirth, and how the rising ash symbol found there doubles as a depiction of an ash tree rising from the impact zone. This symbolic ash tree in the ground zero pyre is reference to the ash tree Yggdrasil, and thus to the weirwoods. This line of ash tree symbolism stacks on top of a separate line of burning weirwood symbolism that also exists at these ground zero Lightbringer bonfires, such as the burning sea dragon gods, the literal burning tree that Arya sees in the holdfast near the Gods Eye, or the logs with secret hearts touched by fire at Dany’s alchemical wedding.

Both lines of weirwood symbolism at ground zero are preceded by the Ironborn legend of the Storm God’s thunderbolt setting the tree ablaze, which seems to place a weirwood symbol – the burning tree – at the site of a meteor impact (the place where the thunderbolt landed). The sea dragon legend does the same: the part about a slain sea dragon that could drown whole islands is almost certainly referring to a dragon meteor which caused tidal waves, but the “ribcage” of the sea dragon, called “The Bones of Nagga,” seems to be made of petrified weirwood. Grey King seems to have sat in a weirwood throne of some kind amidst these weirwood “bones,” and for that reason and several others, was probably a greenseer.

Both of these Ironborn myths conflate meteor impacts and weirwood symbolism, and both specifically involve the Grey King acquiring some kind of divine fire, the fire of the gods. This is of course the primary theme which unites the flaming sword / Lightbringer ideas and the burning tree / weirwood ideas: mankind acquiring the fire of the gods.

What is all this weirwood symbolism doing at the site of the meteor impacts? Well, that’s the question we are working on answering, piece by piece. The first thing we figured out was that it has to do with Azor Ahai being some sort of greenseer who undergoes a death and rebirth transformation experience, and that this likely involves both moon meteors and weirwoods – though we haven’t figured out exactly how that works.

The next big piece of the puzzle in regard to the weirwood symbolism found at the Lightbringer bonfires was the discovery of the correlation between the weirwood trees and the moon, because of the fiery womb role they both play – they both get impregnated and wed by Azor Ahai, and both give birth to some kind of reborn Azor Ahai.

King Bran

✧ Greenseer Kings of Ancient Westeros

✧ Return of the Summer King

✧ The God-on-Earth

End of Ice and Fire

✧ Burn Them All

✧ The Sword in the Tree

✧ The Cold God’s Eye

✧ The Battle of Winterfell

Bloodstone Compendium

✧ Astronomy Explains the Legends of I&F

✧ The Bloodstone Emperor Azor Ahai

✧ Waves of Night & Moon Blood

✧ The Mountain vs. the Viper & the Hammer of the Waters

✧ Tyrion Targaryen

✧ Lucifer means Lightbringer

Sacred Order of Green Zombies A

✧ The Last Hero & the King of Corn

✧ King of Winter, Lord of Death

✧ The Long Night’s Watch

Great Empire of the Dawn

✧ History and Lore of House Dayne

✧ Asshai-by-the-Shadow

✧ The Great Empire of the Dawn

✧ Flight of the Bones

Moons of Ice and Fire

✧ Shadow Heart Mother

✧ Dawn of the Others

✧ Visenya Draconis

✧ The Long Night Was His to Rule

✧ R+L=J, A Recipe for Ice Dragons

The Blood of the Other

✧ Prelude to a Chill

✧ A Baelful Bard & a Promised Prince

✧ The Stark that Brings the Dawn

✧ Eldric Shadowchaser

✧ Prose Eddard

✧ Ice Moon Apocalypse

Weirwood Compendium A

✧ The Grey King & the Sea Dragon

✧ A Burning Brandon

✧ Garth of the Gallows

✧ In a Grove of Ash

Weirwood Goddess

✧ Venus of the Woods

✧ It’s an Arya Thing

✧ The Cat Woman Nissa Nissa

Weirwood Compendium B

✧ To Ride the Green Dragon

✧ The Devil and the Deep Green Sea

✧ Daenerys the Sea Dreamer

✧ A Silver Seahorse

Signs and Portals

✧ Veil of Frozen Tears

✧ Sansa Locked in Ice

Sacred Order of Green Zombies B

✧ The Zodiac Children of Garth the Green

✧ The Great Old Ones

✧ The Horned Lords

✧ Cold Gods and Old Bones

We Should Start Back

✧ AGOT Prologue

Even setting aside the issue of Azor Ahai, the greenseer / weirwood relationship functions this way: the weirwood is the host, and the greenseer the invader. The greenseer sacrifices his physical body to the tree, either by allowing it to slowly consume his or her flesh as Bloodraven is being consumed by the trees, or by our hypothesized scenario where the first seers to enter a weirwood were actually killed in order to go inside it, with the heart tree drinking and tasting the blood as Bran does in his last vision through Winterfell’s heart tree in ADWD. The greenseer allows himself to be consumed by the tree, but in doing so actually invades the tree’s consciousness and becomes reborn inside the weirwoodnet, a part of the godhood. The greenseer, in general, represents the fire animating the weirwood and the heart in the heart tree, but he essentially has to die to get in there.

The symbol that best depicts this is that of the “ember in the ashes.” Mel compares Azor Ahai’s rebirth to an ember in the ashes which can spark a great blaze, like a kind of hell phoenix. However, the idea of Azor Ahai lurking inside the ashes turned out to also be a play on the fact that Yggdrasil is an ash tree, thus implying Azor Ahai as being inside the symbolic ash tree, which are the weirwoods. He’s the ember in the ashes and the ember in the ash tree, just as the greenseer is the fire or heart in the heart tree.

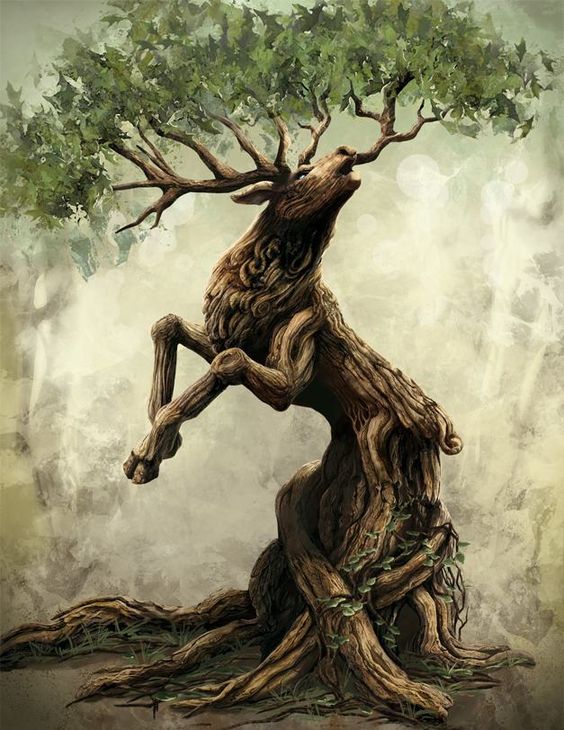

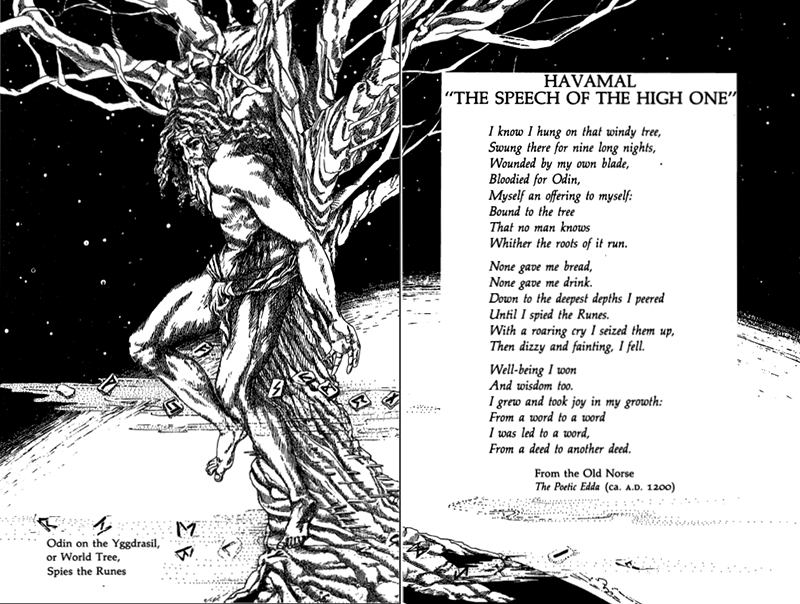

Mel’s wording is also suggestive of Azor Ahai being reborn from the ash tree and emerging to start a great fire, completing the in and out again journey of Azor Ahai and the weirwoodnet. He seems to undergo death transformation to get in, as Odin did, and is born again when he reemerges, as Odin fell from the tree after hanging in a trance for nine days and finally spying and seizing up the runes. Thus, you can see that the weirwoods and Yggdrasil both play the role of a tree tomb and womb which allows sorcerers to transcend death and experience some sort of magical rebirth, and this tree womb idea will be the focus of today’s episode.

Yggdrasil isn’t only a vehicle for Odin’s rebirth – the idea of old Yggy as a more literal tree womb is actually a prominent part of its lore, as it happens. The only two people who survived Ragnarok did so by hiding inside Yggdrasil’s trunk, then reemerging after a time to restart civilization. From tree-tomb to tree-womb. This would seem to correlate well to our ideas about greenseers being reborn through the weirwoodnet, since the mythical ash tree is both eating people and acting as a womb from which people can be reborn. In a more general sense, it also seems similar to the idea of the children and their greenseer magic being needed to ensure the survival of humanity after the Long Night. The Long Night borrows a lot from Ragnarok as a catastrophic event that ends one world age and gives birth to the next, so to the extent that the greenseers preserved that flame of life to take root again in the spring, they are playing that same protective womb role for humanity. Plus, they might have literally hidden the First Men in their caves, for a more literal depiction of this theme.

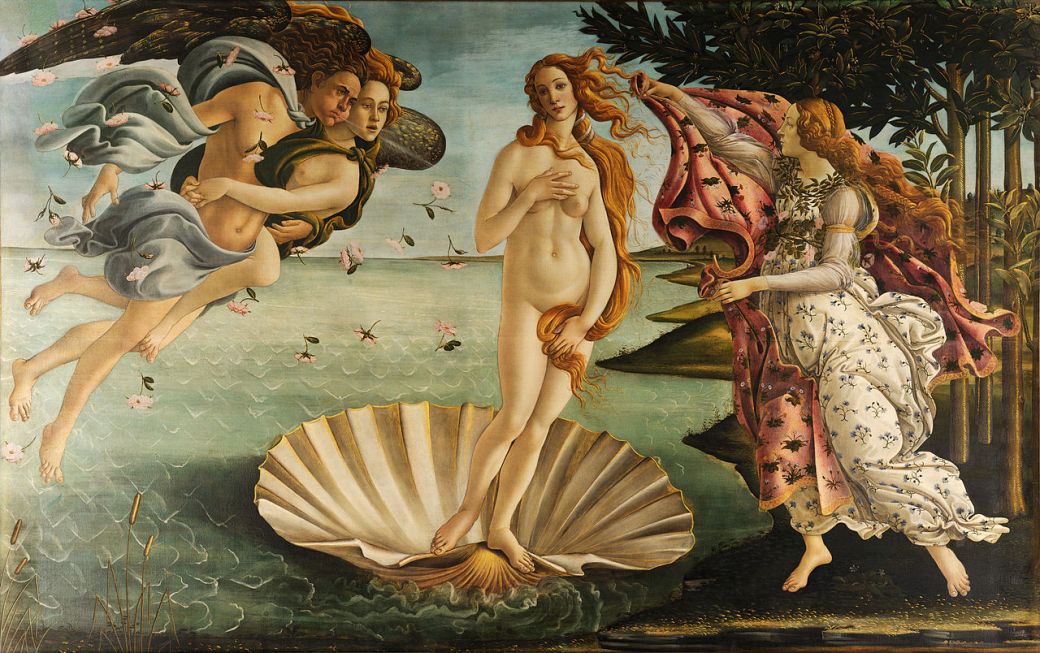

Now, it turns out this tree-womb and tree-woman stuff in relation to the ash tree is not limited to Yggdrasil and Norse myth. Rather, I have found that the tree lore that has grown up about the ash tree is pretty amazing, and goes well beyond its identity as Odin’s cosmic world tree. For example, according to Celtic druid traditions, the ash tree is seen as the world-mother tree, the feminine counterpart to the masculine oak tree, the all-father tree. This has a lot to do with the bark of the two trees – oak tree bark is heavily gnarled and ridged, while ash trees are comparatively smooth. The title of this essay – Venus of the Woods – is one of the well-known names given to the ash tree. It’s hard to determine exactly why this is so, apart from its general beauty and smooth bark – the best answer I can find is that because it is last to get it’s leaves in the Spring and the first to drop them in the Fall, the tree is often naked… naked and tall and beautiful, like a Venus. I myself wonder it has something to do with one of its most distinctive features: the tips of its branches always curl upward at the end, no matter how low the rest of the branch might droop. So, like Venus, there is a distinct falling and rising action.

Whatever the reason, the ash tree as a Venus sure fits well with the idea of the weirwood as a burning tree that is created when a falling Evenstar lands on it. It sure jumped off the page at me when I read it, I can tell you that! Our theory holds that the Nissa Nissa moon turns from moon maiden to falling Evenstar after it ingests the comet, and back to morningstar again when she rises from the ashes. This rising ash creates the image of the ash tree, the Venus of the woods. And that’s just the point of this episode – the tree in the pyre is in many ways synonymous with Nissa Nissa, the fallen and reborn Venus.

One of our Guardian of the Galaxy patrons and Westeros.org chat buddies gets a large hat-tip here, and that would be the afore-mentioned Lady Jane of House Celtigar, the Emerald of the Evening and captain of the dread ship Eclipse Wind, Guardian of the Crone’s Lantern. She brought the following to my attention, and an additional hat-tip to Unchained, for reminding me about this after I had forgotten about Lady Jane’s hat tip a couple months earlier. In Greek mythology, there is a variety of tree nymph called the Meliae or Meliai who are tied to ash trees – they are essentially like dryads, like a spirit of the ash tree. They supposedly gave birth to one of the older races of man, the bronze generation, who were a warlike people that the Meliai tree nymphs armed with spears of ash wood from their ash trees. The Meliai also nurtured their bronze children with the honey from their trees, and elsewhere, it was some Meliai who nurtured Zeus on the same nectar when he was an infant.

As it happens, the origin tale of the Meliai actually overlaps with that of Aphrodite, also known as Venus – she who was born in the seafoam from the severed testicles of Ouranos, a legend we discussed at the beginning of Garth of the Gallows. It turns out that while the seed from Ouranos created Aphrodite, the blood from his castration wound created a few other beings, among them the Meliai. It’s not hard to see how this translates into ASOIAF – the falling blood of a wounded god would be our rain of ‘moon blood’ and bleeding stars which were the pieces of the slain moon goddess, and instead of that blood giving birth to tree nymphs, it created the burning tree. What we are going to see here today is that the burning tree and Nissa Nissa have an awful lot of overlap, so it’s pretty great to know there is a precedent for divine blood falling from the heavens and giving rise to magical ash tree women.

The ash tree has specific associations with burning. It’s most likely that it’s name was chosen in part because it makes for such excellent firewood – it’s able to burn as soon as it is cut down, even while still ‘green,’ and the resulting flame is bright and hot. The traditional yule log was supposed to be of ash wood, and as it happens, one of Odin’s many names is “Yule Father.” Odin was one with his ash tree Yggdrasil, so this makes sense.

We also need to consider the rowan tree, because rowan trees are also known as mountain ash (although they are actually not related to the ash tree – they just look somewhat similar and so are both called ash). Martin has made specific reference to both rowan trees and mountain ash trees in the story, and as you will see, it would appear that he is incorporating some of the folklore around these trees as well. The rowan is widely known in Europe as the “witch tree,” for several related reasons having to do with supposed magical properties and the fact that its red berries appear to have a five pointed star – like a pentacle – on their underside. Rowan trees and ash trees were both among the top choices for magic wands, were thought to convey magical protection, and that sort of thing. Ash wood in particular was the choice for making runestaffs in Norse mythology, and that is almost certainly why J. R.R. Tolkien chose to make Gandalf’s staff one of ash wood (f un fact!)

And lest I fall down on my job, I should point out that the five pointed stars on the red rowan berries also suggests red stars in the canopy of the the world ash tree. The red, five-pointed weirwood leaves serve much the same purpose.

the satan-worshipping fruit of the rowan tree

image courtesy Bob Bell from the Out and About Photo Blog

We’re going to explore some of this tree folklore a bit further as we go along, but already you can see some of the pieces we are working with in the ash and the rowan: a Venus of the woods tree and a witch tree; runestaffs and red star fruit; ash trees that give birth to humans and ash trees that are tied to tree nymphs who dole out ash wood spears. And did I mention that the druids were said to have burned rowan branches before a battle to invoke the aid of the sidhe? That’s significant because George has referred to the Others as a kind of icy sidhe. We already suspect that the Others are tied to the weirwoods, the symbolic burning ash trees, so… we’ll have to follow up on that.

With that short introduction into the relevant tree lore out of the way, let’s dig into some ASOIAF and watch moon maidens turn into weirwoods before our very eyes.

A Treed Cat

This section is brought to you by Lord Brandon Brewer of Castle Blackrune, Sworn Ale-smith to House Stark, Grand Master of the Zythomancers’ Guild, Keeper of the Buzz, and earthly avatar of Heavenly House Sagittarius

Sooooooooo……. Is Nissa Nissa a weirwood tree?

Well… Yes!.. and… no. They do seem to correlate to each other, just as Nissa Nissa correlates to the moon. However I think Nissa Nissa does kind of have to have been a real woman in some sense, because reproduction is probably the most important manifestation of this whole business about cycles and transformations, and Azor Ahai really can’t pass on his magical genetics to anyone unless he reproduces with Nissa Nissa. So she’s definitely a woman on some level.

But like Nissa Nissa, and like the moon which gave birth to dragons, the weirwood tree also seems to play the role of a fiery womb which gives birth to Azor Ahai reborn. Before you can give birth to Azor Ahai reborn, you have to wed Azor Ahai, that is indeed the case with the moon, which was wed by the sun, and with Nissa Nissa, supposedly the wife of Azor Ahai, and it’s the case with the weirwoods, wed by Azor Ahai when he theoretically became a greenseer. That’s the kind of thing which is probably not a coincidence.

Then there is the fact that most of our prominent Nissa Nissa moon maidens in the story… well, they sort of look like weirwoods to some degree, with pale skin and red, ‘kissed-by-fire’ hair. Namely, Melisandre, Lady Catelyn, Sansa, Ygritte, Daenerys when her hair catches on fire, and a few other minor characters. A tree’s leaves are like its hair, and the red leaves of the weirwoods are described as “a blaze of flame,” so Nissa Nissa moon maidens with red, kissed by fire hair are already off to a good start to looking like a weirwood… and then Martin seems to contrive ways for them to acquire the symbolism of bloody hands, bloody or red eyes or tears, and a bloody mouth. These “weirwood makeovers” will of course always take place in the middle of a Lightbringer forging scene, as you might expect. In particular, they will happen in scenes where people are usually attacking these weirwood moon maidens with Lightbringer weapons in a recreation of the comet hitting the moon, the thunderbolt hitting the tree, and the greenseer going into the wierwood.

You remember that movie Stigmata? The movie isn’t important, it’s the concept – the stigmata is when someone, usually a Christian believer, manifests the wounds of Christ – nail marks in the hands and feet, the wound in the side, and the cuts on the brow from the crown of thorns. These weirwood makeovers are kind of like the stigmata – our Nissa Nissa moon maidens seem to manifest the signature wounds of the heart tree while being symbolically stabbed or impregnated by a comet or Lightbringer symbol. We will check out some great ones today and save a couple others for the future, after we have introduced the next concept. It’s pretty startling how consistent it is – once you notice the pattern, it really stands out.

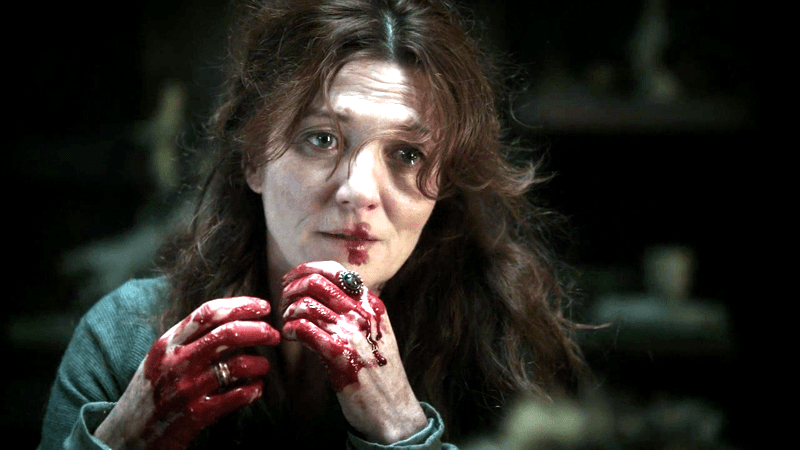

Excepting Daenerys, who we will be setting aside until the next episode, Lady Catleyn and Melisandre seem to be the two best and most detailed examples of Nissa Nissa moon maidens manifesting this weirwood stigmata, so we will be spending the most time with them. First comes Lady Catelyn. She has two scenes that work together: the catspaw assassin’s attempted murder of Bran, and the Red Wedding, and these two scenes together layout the complete set of weirwood maiden symbols. We’ll also wave a quick hello to Lady Stoneheart, since she is so fond of hanging people, and since her character is basically a continuation or reverberation of the Red Wedding.

The catspaw scene starts with the catspaw assassin himself, who is a great symbol that we will see repeatedly in the various scenes we will examine today. The catspaw assassin was sent by Joffrey, a solar character, so his catspaw nickname is actually an identification of his symbolic role – he is acting as the paw and claw of the sun, as the sun’s weapon or executioner. That is pretty easy to identify as the comet which struck the moon, which can also be though of as the sun’s sword or the sun’s “long claw.”

Now, we’ve talked a few times about the idea of the original comet being white and silver, like normal comets, perhaps suggested by the the description of Lightbringer being “white hot” and “smoking” before stabbing Nissa Nissa and being turned red. The catspaw assassin seems to fit this description, being described as “gaunt, with limp blond hair and pale eyes deep-sunk in a bony face.” His knife, however, is dark Valyrian steel with a black dragonbone hilt. That’s very like a black comet core with a white tail, exactly how regular comets look, with the dragon associations of the hilt and steel making this an especially terrific symbol of a dragon comet. Ghost and Jon combine to form a similar image as they rush the weirwood grove – Jon is a black sword with a white shadow at his side, as Ghost is called in that scene. Jon’s spirit inside Ghost is more of the same – a black sword brother inside a streaking white shadow. Jon’s sword, Longclaw, shows us a similar pattern, with a black blade and white wolf head pommel.

Returning to the catspaw assassin, we see that he’s also remarked upon to be a “stranger” at Winterfell, and the Stranger of the Faith of the Seven is known as “the wanderer from far places,” which I’ve always thought of as a perfect description of a comet (a wandering star from far places). The assassin is a stranger with a dragon-tipped claw, sent by the sun to kill – that’s the comet. Jon too is called a stranger and has Stranger symbolism, and he is a comet person in many scenes.

In Weirwood Compendium 4, In a Grove of Ash, I asserted that comets and meteors that penetrate moons and trees are symbolic of skinchangers, who insert their spirits into animals and trees. The catspaw should therefore show us skinchanger symbolism as well, and here’s what we find: he slept in the stables with the horses and reeks of the stables, and we know that Yggdrasil can be a horse. His horsey smell and origin from the stables also makes him a kind of horse comet, and we know that the Dothraki interpret stars and comets as fiery horses, so that’s a good fit for both skinchanging and comet implications. The folks at Winterfell also found “ninety silver stags in a leather bag buried beneath the straw” where the assassin was hiding, which sounds like sacrificed stag-man symbolism. The stags are buried in a leather sack, meaning inside a skin, and buried like a dead body, reinforcing the sacrificed stag symbolism. One thinks of the hanged men outside the Inn at the Crossroads, a.k.a. the Gallows Inn, a.k.a. the inn that symbolizes a weirwood, and we think of the young inkeep Jeyne Heddle demanding a ‘sacrifice’ of silver stags to get in to the inn.

We’re actually going to return to that inn in a bit for a *weirwood makeover, as a matter of fact, but the point is that stags or green men must be sacrificed to enter the weirwood. It’s almost as if the buried sack of stags is like the sacrificed body of the skinchanger, and the assassin is like his spirit, going into the trees.

Cat is of course the Nissa Nissa figure and the weirwood figure. As Cat sees the assassin and turns to the window to scream for help, we see her acquire two main parts of the weirwood makeover in quick succession: the bloody hands and bloody mouth. We’re also going to see the important cannibalism symbolism, which I would say alludes to the weirwoods consuming the bodies and spirits of the greenseers strung up in their roots, and also to the general practice of human sacrifice to weirwood trees.

She reached up with both hands and grabbed the blade with all her strength, pulling it away from her throat. She heard him cursing into her ear. Her fingers were slippery with blood, but she would not let go of the dagger. The hand over her mouth clenched more tightly, shutting off her air. Catelyn twisted her head to the side and managed to get a piece of his flesh between her teeth. She bit down hard into his palm. The man grunted in pain. She ground her teeth together and tore at him, and all of a sudden he let go. The taste of his blood filled her mouth. She sucked in air and screamed, and he grabbed her hair and pulled her away from him, and she stumbled and went down, and then he was standing over her, breathing hard, shaking. The dagger was still clutched tightly in his right hand, slick with blood. “You weren’t s’posed to be here,” he repeated stupidly.

Alright, a lot just happened. Catelyn gets the bloody hands symbolism when she reaches up to pull the assassin’s knife from her throat and cuts her hand. Next she bites down hard on the flesh of the assassin’s hand and gets the taste of his blood in her mouth, giving her the bloody mouth of a heart tree with a side of flesh-eating weirwood symbolism. When a weirwood / moon figure like Cat eats a comet symbol like the assassin – his hand at least – that is a depiction of Azor Ahai going into (being eaten by) the trees, and this of course parallels the moon swallowing the sun’s comet. It’s just like when the woods swallowed the last slice of sun, all that stuff we talked about last time. Accordingly, the comet / assassin figure has the bloody hand symbol too now – he is symbolically merging with the weirwood / moon figure and so is sharing the same weirwood bloody hand symbolism. We are going to see that pattern throughout this episode.

courtesy HBO’s Game of Thrones

Just to get extra tricky, consider this: the catspaw is like the solar lion’s hand – his paw – and Lady Cat is, in a manner of speaking, ‘eating’ the hand of the catspaw. That would be the paw of the paw of the king lion, eaten by another cat, like some sort of macabre Russian doll trick. In turn, the catspaw assassin also sliced up Cat’s hand – her paw – so you could say that the catspaw bit Cat’s paw and then Cat bit the catspaw’s paw right back. At least, that’s the kind of thing you’d say if you were raised on Dr. Seuss as I was. And that is what I call fractal symbolism.

Notice the line about the assassin cursing in Cat’s ear – it might be nothing, or it might imply the comet and meteors cursing the things they struck, which does make a certain amount of sense.

A moment later the assassin’s blade is clutched in his hand, now covered in Catelyn’s blood, in order to give us the idea of Lightbringer turned red by Nissa Nissa’s blood. We’ll see that type of symbol in most of the scenes we look at – either the weirwood moon maiden reddening a sword with her blood, or else a sword being taken from the weirwood moon maiden like Gram being pulled from the Brandstokr tree. We saw it at the burning of the Seven on Dragonstone when Stannis pulled Lightbringer from the burning wooden chest of the Mother’s statue. And don’t forget that the catspaw assassin’s blade is Valyrian steel, spell-forged in dragonfire, and blood-soaked Valyrian steel is about as close to actual Lightbringer as we get. Also, Catleyn has fallen to the floor, which of course depicts the fall of the moon maiden from heaven after her encounter with the comet.

Next up in terms of symbolism, we have the rising smoke. Bran’s wolf, Summer, is elsewhere described as looking like “silver smoke,” so when he rises from the ground level to the tower chamber to rip out the assassin’s throat, we can see that as the rising smoke cloud which blots out the face of the sun:

Catelyn saw the shadow slip through the open door behind him. There was a low rumble, less than a snarl, the merest whisper of a threat, but he must have heard something, because he started to turn just as the wolf made its leap. They went down together, half sprawled over Catelyn where she’d fallen. The wolf had him under the jaw. The man’s shriek lasted less than a second before the beast wrenched back its head, taking out half his throat.

Summer is a shadow made of silver smoke, which is the rising smoke and ash. It would be nice if Joffrey, the sun person who sent the comet assassin, were here in person to have Summer rip out his throat, but since that’s impossible, the assassin would seem to play the sun role too when he’s killed by the smoke and shadow wolf. Of course Joffrey’s solar face is eventually darkened at the Purple Wedding by Cat’s daughter Sansa, with her moonlight-drinking, poison black amethysts, seen by the Ghost of the High Heart as “a maid at a feast with purple serpents in her hair, venom dripping from their fangs.” Not only do those dark purple gems turn Joff’s face a purple to match their own coloring, they are actually linked back to smoke and ash, because the poison at work, “The Strangler,” is from Ash-shai, and is itself made by a process which involves being thickened by ash, according to the late, great Maester Cressen. You can see how tightly the symbolism correlates here – ash and smoke are what kill the sun, whether it’s a silver smoke shadow wolf or the ashy poison from Asshai.

The idea that the smoke and ash which swallowed the sun can be associated with a wolf like Summer makes for a nice callout to the norse myth of Skoll and Hati, the wolves who swallow the sun and moon at Ragnarok and cause the lights to go out, a myth I probably should have mentioned by now (Norse mythology buffs have probably been cry out “what about Skoll and Hati?!” for at least a couple of podcasts now, so here you go). Smoke-dark Grey Wind sends the same message as a wolf made of sun-darkening smoke, and as we discussed extensively last time, Ghost is a weirwood wolf that will swallow Jon the sun king, just as the woods swallowed the sun in the weirwood grove of nine scene. There’s even a forest called the Wolfswood that does the sun-swallowing trick too, but we’ll quote that scene in a bit. You see the point though – a wood named after a wolf is getting to the same idea as a wolf the color of a weirwood tree, and everybody is hungry for a piece of the sun.

Returning to the Catleyn scene, right after the line about the wolf “taking out half his throat,” it says that “his blood felt like warm rain as it sprayed across her face.” That gives us two symbols we know well – the red rain of bleeding stars meteor shower, and the bloody face to suggest the bleeding face of the heart trees. Perhaps most importantly, it continues the symbolism of Cat as a blood-drinking, flesh-eating weirwood, as the assassin’s blood is offered to her like the captive before the heart tree. I believe this would also be a Meliai reference – weirwood Cat is created the blood that falls like rain, just as the Meliai were created by the blood of the sky god Ouranos, which fell from heaven like rain. Afterwards, Catelyn’s scalp is left raw and bleeding where the assassin ripped out a hank of hair – that’s kissed by fire hair, which is now blood and fire hair to match red blood and fire canopy of the weirwoods.

Cat’s makeover is complete – bloody hands. Bloody mouth. Blood and fire hair. It’s the portrait of the burning tree I was talking about. She doesn’t cry bloody tears – that comes at the Red Wedding – but her face is covered by the assassin’s blood, giving her the bloody face of a weirwood.

The other ‘Catleyn as a weirwood’ clues here have to do with her speech: when she first sees the assassin, her words stick in her throat, “the merest whisper,” like a whispering weirwood, and when they find her later, her laughter “dies in her throat.” Some of the faces on the wierwood heart trees appear to be laughing, as we saw in the grove of nine, but more important is the silent scream of the weirwood – the weirwood bark, if you recall. It’s the sound that Ghost makes, the one that only Jon heard when he went back and found newborn Ghost by himself in the snow. The silent scream implies someone who cannot speak, and the bloody mouth might suggest someone whose tongue has been torn out, which overlaps nicely with cutting the throat of a sacrifice.

You will recall that cutting someone’s throat is sometimes referred to as giving them a “red smile,” just like a laughing weirwood has a red smile, and just like bloody-mouthed Cat with her mad, dying laughter. Additionally, the assassin tried to cut Cat’s throat and nearly succeeded, which also works to imply the weirwood figure having their throat cut and thus being given a red smile.

It’s almost as if both the sacrifice and the weirwood itself have their throats cut, as if both are sacrificed to create the burning tree person – you’ll notice that the catspaw assassin, the comet person trying to merge with the weirwood by giving it a face, has his throat torn out by the wolf. Just as both Cat and he have the bloody hand, they both get the throat-cutting / red smile symbolism – because the are symbolizing the merging of the greenseer and weirwood. Again we might see a parallel with Ghost and Jon, as Jon had his throat cut and his spirit sent into his weirwood-colored wolf, who already has a red smile, just like a greenseer dying to go into his tree. Also, Ghost and Jon may both ultimately end up dying to create the merged wolf-man skinchanger zombie Jon. Of course, all of this draws a broader parallel to the sun and moon which destroy each other to create Azor Ahai reborn meteors.

Now, you can’t really cut a weirwood’s throat, but think about the symbol of the red smile: for a human, it means a throat cutting, but for a weirwood, a red smile is just a part of its face. Thus, cutting a weirwood figure’s throat is like to giving a weirwood a red smile, and that probably equates to giving a weirwood a face, complete with bloody red smile. We’re going to see a lot of throat cutting today, so I want to lay this out right at the beginning.

There’s another great weirwood symbol present here at Winterfell, and this great find comes to us courtesy of Ravenous Reader, the Poetess. It has to do with the library. Following the incident, the catspaw assassin is immediately believed to have set fire to the library tower as a distraction before his main attack. Whether he did or not, a library is made of paper – meaning wood – and is a repository of knowledge. Thus, it makes an outstanding symbol of the weirwoodnet, which is basically a library made of wood (and just fyi, the library / weirwood symbolism does seem to be expressed elsewhere – take a look at the scrolls or books in any scene where they are discussed prominently and see what you find). Check out this quote from Jojen to Bran in ADWD:

A reader lives a thousand lives before he dies,” said Jojen. “The man who never reads lives only one. The singers of the forest had no books. No ink, no parchment, no written language. Instead they had the trees, and the weirwoods above all. When they died, they went into the wood, into leaf and limb and root, and the trees remembered. All their songs and spells, their histories and prayers, everything they knew about this world. Maesters will tell you that the weirwoods are sacred to the old gods. The singers believe they are the old gods. When singers die they become part of that godhood.”

The weirwoodnet is directly compared to a library here, and thus the comet assassin figure setting the library tower on fire creates the burning tree symbol, and works in parallel to him wounding Cat and transforming her into a bloody weirwood. Cat sees the burning library, and it says “long tongues of flame shot from the windows,” a familiar symbol in ASOIAF which is also a symbol of the Biblical Holy Spirit, which is nothing if not a representation of the fire of the gods that can live inside the hearts of men. Then “she watched the smoke rise to the sky” – in other words, the smoke is rising from the burning tree, a parallel to the silver smoke wolf rising to Bran’s bedchamber when the fire is set.

Ned likes women who look like heart trees

courtesy HBO’s Game of Thrones

The Red Wooding

This section is brought to you by the Patreon support of one of our high priests of starry wisdom, the Black Maester Azizal, Lord of the Feasible and Keeper of the Records, whose rod and mask and ring smell of coffee.

Next we come to the Red Wedding. We are not going to do a breakdown of the entire Red Wedding, because that’s a huge undertaking – we’re just going to address Lady Catelyn’s weirwood makeover. We’ll join the action in progress, just after the killing has started. The first thing we will make note of is that Cat takes a projectile wound:

She ran toward her son, until something punched in the small of the back and the hard stone floor came up to slap her.

That turns out to be no ordinary projectile, because a couple of sentences later, it says “Catelyn’s back was on fire.” This might seem like par for the course by now – the moon is set on fire by a projectile – but remember that Cat is also acting out the role of a transformed weirwood being struck by lighting and set afire, so the reference to fire here is doubly important. It helps make her the tree struck by lightning. The spine is also the part of a human which is analogous to a tree’s trunk, so setting Cat’s back on fire is a good depiction of the burning tree. The arrow itself was fired by the musicians in the upper gallery, which makes us think of greenseers who sing magical songs to call projectiles down from the heavens, a la the Hammer of the Waters fable.

Next, Cat gets the bloody mouth:

Her limbs were leaden, and the taste of blood was in her mouth.

Leaden limbs are stiff limbs, kind of like a tree perhaps, but more importantly, lead implies poisoning, which is an aspect of the lightbringer comet (think of the black amethysts snakes, or Oberyn’s poison-tipped sunspear). The meteors are a toxic presence on the earth, it would seem, and I think part of the pain and rage on the faces of the trees might indicate a reaction to this toxic presence. I suggested last time that the association with graveworms and maggots that the weirwood roots have might be meant to imply that weirwoods are mitigating and transmuting this toxic effect, and this also works in harmony with the notion of weirwoods as a trap that is restraining a dangerous, minotaur-like monster. I am not set on this but the idea keeps popping up so we will have to keep it in mind. In any case, Cat seems to have a case of lead poisoning and stiff limbs to go with her burning spine and bloody mouth, so let’s keep going.

Next, as Robb is shot with crossbow bolts and many Starks and friends are cut down, Catleyn takes Walder Frey’s lackwit grandson Jinglebell hostage, and there’s a direct tie made to the first scene with the catspaw assassin.

When she pressed her dagger to Jinglebell’s throat, the memory of Bran’s sickroom came back to her, with the feel of steel at her own throat.

I believe this link is created between the two scenes because the two scenes are similar, and express the same ideas involving Cat turning into a weirwood. Now when Robb is killed, Cat cuts Jinglebell’s throat, and it says that “the blood ran hot over her fingers.” That’s a case of the bloody hands to go with the bloody mouth, the makings for a solid case of weirwood stigmata. Just as when Summer tore out the Cat’s paw assassin’s throat and the blood was like warm rain on Cat’s face, this is a depiction of human sacrifice to the weirwood trees.

As for Jinglebell, he’s playing the role of sacrifice, and his real name is… Aegon, actually. You can’t say the name Aegon without thinking of Aegon the Conqueror, who rode a black dragon, Balerion, and wielded the sword Blackfyre. Aegon the Conqueror is a pretty clear dark solar Azor Ahai reborn figure, and therefore what we are seeing with Jinglebell Aegon’s sacrifice to Cat the weirwood goddess is yet another implication of Azor Ahai being sacrificed to the weirwood. Immediately following this sacrifice, Cat will be give the “bloody face” part of the wierwood makeover, which seems to be the right sequence – a greenseer is sacrificed, the tree is given a face, and the spirit of the greenseer enters the tree. We will see this depicted in a moment by Catleyn losing her wits after killing Jinglebell, as if she is absorbing his fool’s spirit.

So right after she cuts his throat is grisly fashion, cutting down to the bone, it says “finally someone took the knife away from her.” This is showing us the ‘Lightbringer being pulled from the burning tree’ symbol which we introduced a few moments ago, which I told you would appear in most of these scenes. Next, Catelyn goes mad and rakes her own face with her fingernails:

The tears burned like vinegar as they ran down her cheeks. Ten fierce ravens were raking her face with sharp talons and tearing off strips of flesh, leaving deep furrows that ran red with blood. She could taste it on her lips.

This sounds very much like a face being carved in to the weirwood tree! Her face is literally being carved here, the blood running through furrows on Cat’s face. The word “furrow” is suggestive of planting and sowing, as if the moon blood were about to grow something, and again, this is as literal a face-carving as any human undergoes in ASOIAF. The word furrow is also notable because the phrase “furrows of Odin” is a phrase which means “runes.” In Norse languages, there exists something called a kenning spelled the same way as House Kenning of the Iron Islands) which is defined as a circumlocution (an ambiguous or roundabout figure of speech) used instead of an ordinary noun. Instead of saying rune in a poem, the writer might say “furrows of Odin” and everyone would understand that he meant rune. A rune is carved in wood or stone – again, ash trees are the best choice for rune-staffs – which is why it can be a furrow.

In other words, I think Martin is drawing a link here between face carving and Odin’s runes, which of course makes a ton of sense, since the wedding of a greenseer to a weirwood is the ASOIAF equivalent to Odin’s hanging on the tree. We’ll see another kenning referenced in Cat’s death in just a moment, actually.

As for the sharp implements doing the face carving – the black ravens- they are black meteor symbols, so that’s probably why George chose to use them as a metaphor here. It’s another way to show the moon meteors setting the tree on fire, and specifically in conjunction with it receiving a face. As Ravenous Reader points out, it also makes her a better weirwood tree – she has ravens perching on her!

Our poor treed Cat has a bloody mouth again too, this time viscerally tasting it on her lips in a way that reminds us of Bran watching the human sacrifice through Winterfell’s heart tree, where it said that “Brandon Stark could taste the blood.”

Then we get the bloody tears image and mercifully, Cat’s death:

The white tears and the red ones ran together until her face was torn and tattered, the face that Ned had loved. Catelyn Stark raised her hands and watched the blood run down her long fingers, over her wrists, beneath the sleeves of her gown. Slow red worms crawled along her arms and under her clothes. That made her laugh until she screamed. “Mad,” someone said, “she’s lost her wits,” and someone else said, “Make an end,” and a hand grabbed her scalp just as she’d done with Jinglebell, and she thought, No, don’t, don’t cut my hair, Ned loves my hair. Then the steel was at her throat, and its bite was red and cold.

Here we see the mutual throat cutting of greenseer and weirwood, just as we saw when both Cat and the catspaw got the throat cutting symbolism in Bran’s sickroom. Just like in the sickroom, we find Cat with the mad laughter again, as her laughter mixes with her screams, thereby also suggesting the agony and ecstasy of Nissa Nissa. This is the part I mentioned a moment ago about Cat losing her wits, signifying that she is symbolically absorbing Jinglebell’s fool spirit. We are going to see this a bunch of times today – the tree and greenseer sharing the same symbolism in the moments that they are depicted as merging. Last time it was a Cat and a catspaw, both with bloody hands and throat cutting symbolism, and this time we have two lackwits getting their throats cut in identical fashion.

Most notable are Cat’s bloody tears, which run together with her white tears, thus completing the basic part of the weirwood makeover, Twins Edition. Usually the ‘bloody tears of the weirwood’ symbolism is achieved symbolically, with eyes red from crying or some such, because Martin can’t literally carve out a moon maiden’s eyes every time he wants to symbolize the weirwood stigmata. This, however, is one of the instances of real, genuine bloody tears, so together with the real, genuinely painful sounding face-carving, this one of the very best examples of a Nissa Nissa moon maiden getting a weirwood makeover. Note also that her tears burn like vinegar, creating the burning tears / burning blood symbolism.

When Cat raises her bloody hands, she’s essentially striking a tree pose, as if she is actually turning into a tree in that moment – the moment just before she is given her red smile. Martin serves us up a juicy one next and turns the blood into worms crawling along her arms and under her clothes, which certainly reminds us of the graveworm-like weirwood roots that do the exact same thing to Bloodraven, weaving over, around and through him.

But wait! There’s more. When we talk about bloody red worms, we must mention the only red dragon in all of ASOIAF – Caraxes, the Bloodwyrm, ridden by that same Daemon Targaryen who took Bloodstone Island for his seat. A red dragon is of course primarily a symbol of Lightbringer the red sword or red comet, and that fits perfectly with what is going on here at the Red Wedding: as Cat transforms into a weirwood, we see a symbol of Lightbringer created from the blood of the dying moon maiden, just as it should. At the same time, it also depicts the weirwood moon maiden merging with Lightbringer the red dragon, which was kind of the theme of the last episode. This is just the same as cat becoming a fool to symbolize her as a weirwood absorbing Jinglebell’s spirit – he’s also an Aegon, and so she is manifesting red dragon symbolism!

The blood worm lines is actually the other kenning I mentioned – “blood worm” is a kenning which means “sword.” We already thought Caraxes the Bloodwyrm was symbolizing the red sword of heroes, so take that as confirmation. This also means Cat’s blood is in a sense turning into swords as she dies, just as the moon explodes and becomes bleeding stars which looks like flaming swords.

If I may say so, this is expert-level symbolism here – Martin has skillfully woven together the moon maiden symbols and wierwood symbols all throughout this scene, with no better example than the blood worm symbol. Dragons, swords, bloody hands, and weirwood roots are all implied by one densely-packed line. The most important take-away here is that Cat is symbolically turning into a weirwood tree, having her face carved, and manifesting Lightbringer and dragon symbolism all in the same moment.

This image is followed up on by the final bit of weirwood stigmata, as Cat is given her red smile. The knife that gives Cat her red smile has a bite that is red and cold, which is interesting. A red bite makes sense as a symbol of the comet striking or biting the moon maiden and of the moon meteor striking the tree, but isn’t Lightbringer supposed to be hot? Yes, it is, but frozen fire is both hot and cold, as is Valyrian steel, which is forged in dragonfire but is repeatedly noted to be very cold to the touch. Comets are the same, appearing to burn hot – but of course comet tails are not made of fire and comets themselves usually contain a lot of ice. Cold red blood also makes us think of the frozen weirwood sap which looks like frozen blood, and that’s a great fit with what is going on in the scene. It’s implying Cat’s red smile is red and cold, like the frozen blood of the weirwood smile, in other words.

The cold red bite of the dagger also reminds me of Mel’s repeated attempts to warn Jon about his own impending red smile (meaning his throat cutting by Wick Whittlestick): “Ice, I see, and daggers in the dark. Blood frozen red and hard, and naked steel. It was very cold.” It’s the cold / frozen red blood symbol again, and as I said, this alludes to Jon’s red smile. And that name, whittle-stick: it’s implying wood carving, with Jon’s neck as the wood. That fits, because Jon is simply taking on the weirwood symbolism of his wolf in the moment he’s about to merge with his wolf, being given a red smile likened to wood-carving.

Ned’s Ice is perhaps the best Lightbringer symbol in the story, and it kind of combines all of these cold red blood ideas we just mentioned – it’s directly compared to the comet, it’s Valyrian steel, it’s named Ice and is the sword most often remarked upon as being cold, and finally, it is soiled with Ned’s blood, reforged, and then appears to have the color of blood frozen in the ripples of its steel. As much as I love Oathkeeper, I don’t want to get too sidetracked here, but I did want to note that the cold red bite of the Frey knife that cuts Cat probably plays into this line of ice and fire / frozen blood symbolism. The broader point is that Cat is wounded by weapons with Lightbringer symbolism in both of the scenes of hers we’ve examined today: first by the catspaw’s Valyrian steel knife, and then by the Frey knife with a cold red bite. Taken with the idea of raven meteors carving her bloody face, and all the bloodworm stuff, I think it’s clear we are being shown that Cat is simultaneously playing the role of Nissa Nissa being stabbed by Lightbringer and the role of a weirwood being entered by Azor Ahai and having its face carved. The basic implication seems clear: the forging of Lightbringer and the carving of the faces seem to be related events.

This idea finds a companion in a description of the red comet that comes to us in Catelyn’s inner monologue. It’s from ACOK to be specific, and here she is speaking with her uncle Brynden Blackfish:

She followed him out onto the stone balcony that jutted three-sided from the solar like the prow of a ship. Her uncle glanced up, frowning. “You can see it by day now. My men call it the Red Messenger . . . but what is the message?”

Catelyn raised her eyes, to where the faint red line of the comet traced a path across the deep blue sky like a long scratch across the face of god.

When we consider that the faces in the weirwoods are the faces of the so-called “Old Gods,” the blades that carve those faces would then be scratching the face of god, as the comet is here. The comet certainly was a scratch across the face of the moon, which can be regarded as a goddess. The weirwoods seem to parallel the moon, and we keep seeing clues about Lightbringer type weapons carving the faces. I think this means the same thing as the story about the thunderbolt setting fire to the tree – something about the meteor impacts and the presence of Azor Ahai and his cronies in Westeros seem to have caused the face carving. In a perfect world, Azor Ahai or Garth the Green or someone like that used a knife made from a black meteor to carve the first face, so add that to the wishlist of things I hope to see in a Bran weirwood vision of the past. But there are actually several ways I can think of that the “Lightbringer and Azor Ahai carving the faces” idea could play out.

Setting aside that literal of an interpretation, meteors are typically used to work magic in Lovecraft stories, or else have their own inherent magical effects (usually magically toxic effects), so it’s more likely than not that the Bloodstone Emperor used his black meteor to work dark magic. Perhaps this had something to do with his ability to enter the trees and set the weirwoodnet ‘on fire.’ The other obvious possibility, which I have mentioned, is that the meteors themselves landed on Westeros and caused a magical reaction from the weirwoodnet, and something about this reaction is tied to the ability of greenseers to enter the weirwoodnet. This would also make sense as the meteor ‘setting the weirwoodnet on fire.’

I’m open to suggestions here – I feel confident that the meteors are linked to the carving of the faces and the greenseers entering the weirwoodnet, but the specifics are more murky. One of the main reasons I think this is because the legend of the Storm God’s thunderbolt setting the tree ablaze and thereby allowing man to possess the fire of the gods strongly implies that the meteors somehow enabled the first greenseers to enter the weirwoodnet. The burning tree fire of the gods is the weirwoodnet, and Grey King couldn’t possess this fire until the thunderbolt struck, so there you go. You see what I mean. He didn’t possess the living fire of the sea dragon until after he slew her, which conveys the same idea.

One final word about kennings: Odin in particular is tied to kennings. He is famous for having over 200 names in kenning form, many of which have obvious implications for ASOIAF such as the Hanged God, Lord of the Gallows, Raven God, Lord of Battles, High One, Battle-Wolf, Grey Beard or Hoary Board, Barrow Lord, Yule-Father, Mask, Hooded One, Wanderer, Father of Magical Songs, Flaming Eye, Shaggy Cloak-Wearer, Wagon God or God of Riders, God of Runes, Mover of Constellations, and many more. That last one is a reference to Yggdrasil as a cosmic axis celestial world tree, I’d like to point out.

So, I mentioned there is a House Kenning – two actually, House Kenning of Harlaw on the Iron Islands, and a splinter branch in service to House Lannister on mainland Westeros called House Kenning of Kayce. You know how the sigil clues work, so I will just give them to you. House Kenning of Harlaw’s sigil is “the storm god’s cloudy hand, pale grey, yellow lightning flashing from the fingertips, on black.” House Kenning of Kayce, meanwhile, has a sigil of “four sunbursts counterchanged on a quartered orange and black field,” meaning two black suns and two orange ones. I’m not sure about the math, but we recognize the black sun symbol as the dark solar king and the Lion of Night, so it’s nice to see a visual confirmation that Martin is indeed thinking about black suns as a general concept.

Now House Kenning of Kayce was founded by an Ironborn warrior known as Herrock Kenning, from the original Harlaw Kennings. His story involves a horn called “the horn of Herrock” which we actually see in the main story, as a Ser Kennos of Kayce accompanies Jaime in the Riverlands and blows the horn at a few crucial times. The horn, weirdly, is described an awful lot like the dragonbinder horn and the supposedly fake horn of Joramun that Melisandre burned: “black and twisted and banded in old gold.” One they blow it to enter Raventree Hall, home of the Blackwoods and their huge, dead wierwood tree.

In other words, all the symbolism attached to either House Kenning leads back to Azor Ahai the dead greenseer and the events of the Long Night. We have the Storm God’s thunderbolt-hurling hand, a horn seemingly meant to remind us of the more significant magical horns in the story, and the black sun symbol. House Kenning of Kayce on the mainland could be seen as kind of turning their cloak from the original Kennings, since they are now loyal to the Lannisters, and this is probably the meaning of their orange sun / black sun sigil – it’s showing us a bifurcation or transformation of the sun.

Anyway, let’s keep it moving.

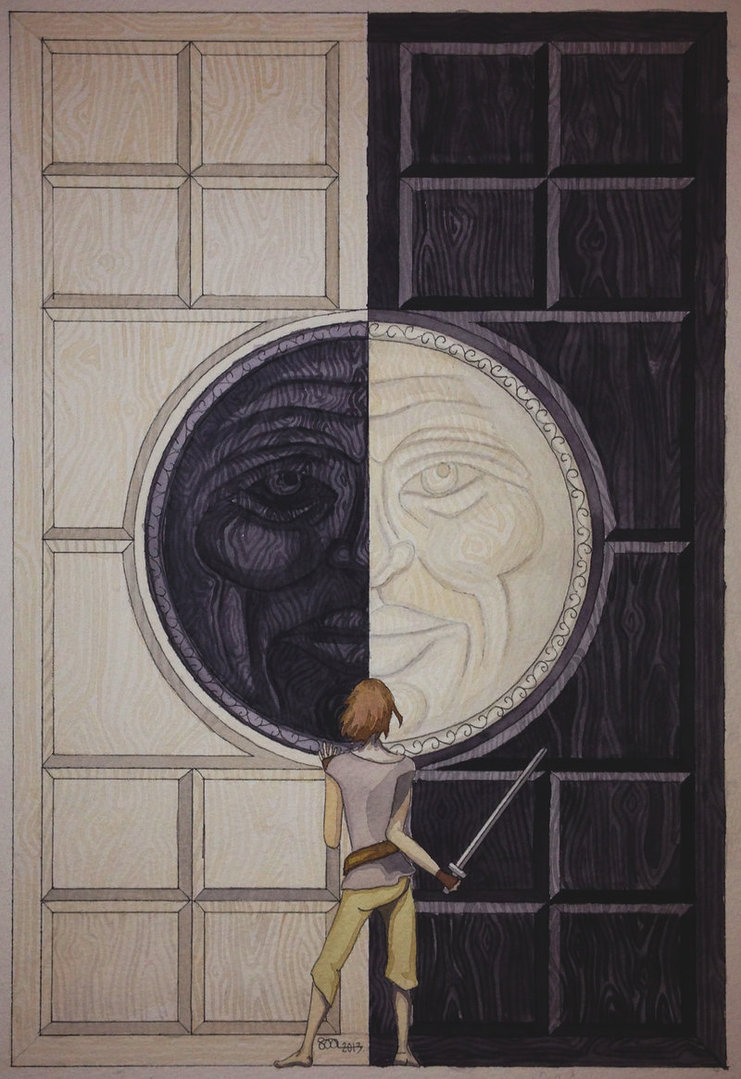

‘Lady Stoneheart’

by zippo514 on DeviantArt

The Silent Sister

This section is generously sponsored by Direliz of Heavenly House Aquarius, the Alpha Patron, a direct descendent of Gilbert of the Vines, the son of Garth the Green who founded House Redwyne.

You know we can’t talk about Lady Cat without mentioning Lady Stoneheart, as much as she enjoys hanging people. She has some great nicknames: The Silent Sister. Mother Merciless. The Hangwoman. Lady-freaking-Stoneheart. Here is Brienne’s encounter with her in Beric’s old cave in AFFC, which serves as a chilling introduction to this character who was just a little too terrifying for HBO :

A trestle table had been set up across the cave, in a cleft in the rock. Behind it sat a woman all in grey, cloaked and hooded. In her hands was a crown, a bronze circlet ringed by iron swords. She was studying it, her fingers stroking the blades as if to test their sharpness. Her eyes glimmered under her hood.

Grey was the color of the silent sisters, the handmaidens of the Stranger. Brienne felt a shiver climb her spine. Stoneheart.

In other words, Cat has become a rather unfriendly psychopomp, who is primarily interested in “feeding the crows,” as one of the Brotherhood says. By the way, the kenning for warrior is “feeder of ravens,” something Martin may have been inspired by. Essentially, Stoneheart is handing out one-way tickets to hell. If the entrance to the weirwoodnet is the entrance to a kind of realm of the dead, then undead Cat is acting as the gatekeeper. Here is a physical description of Stoneheart, a few pages further on:

Lady Stoneheart lowered her hood and unwound the grey wool scarf from her face. Her hair was dry and brittle, white as bone. Her brow was mottled green and grey, spotted with the brown blooms of decay. The flesh of her face clung in ragged strips from her eyes down to her jaw. Some of the rips were crusted with dried blood, but others gaped open to reveal the skull beneath.

Lady Stoneheart still has weirwood symbolism, but it is kind of post-weirwood transformation – she’s no longer such a good fit for the weirwood portrait of the burning tree, having lost the red hair and white skin thing. Her red hair has turned white as bone – which does match the bone white branches and bark of the weirwood – and her pale skin has turned grey and green, a color pairing which has been used to symbolize grey king type undead greenseers. She lives underground in the cave like a greenseer – and symbolically, in the underworld, where a zombie belongs. The words mottled and ragged are used, likening her to the undead scarecrow line of symbolism which also involves fools (who wear motley), thus making a straight line of foolishness and madness symbolism that runs through the scene in Bran’s sickroom, the red wedding, and now here in the cave.

In other words, Stoneheart is more like a tree ghost within the weirwood at this point, much like the Ghost of High Heart or Bloodraven, the latter of which also has that problem with the skull showing through holes in the face-skin that Stoneheart has. Note also that the Ghost of High Heart and Bloodraven both have white hair like Stoneheart, despite having red eyes that still match a weirwood. Catleyn actually does get the red eyes of a weirwood along with her fiery resurrection, and this quote is from that same Brienne chapter:

The woman in grey hissed through her fingers. Her eyes were two red pits burning in the shadows.

Drogon’s eyes are like burning pits and red pits, while the weirwoods have “deep-carved” red eyes which are functionally red pits. This seems like the ember in the ashes / last coal in a dead fire symbolism we examined in the last episode, alluding to an internal fire within Stoneheart, and indeed, Thoros speaks of Beric passing the flame of life into Cat in order to resurrect her. Cat kinda sorta whispers here too – the word used is hissing – and she’s doing so “through her fingers,” almost like a weirwood whispering through it’s branches. Elsewhere in this chapter, her speech is called “halting, broken, tortured” and as “part croak, part wheeze, part death rattle.” That reminds us a bit of Coldhands rattling voice, and plays into the larger theme of having your throat cut and losing your voice that seems to be implied by the weirwoods’ bloody mouths and silent screams.

Then there’s this quote from Lem Lemoncloack in the epilogue of AFFC, the hanging of Petyr Pimple:

“She don’t speak,” said the big man in the yellow cloak. “You bloody bastards cut her throat too deep for that. But she remembers.“

She doesn’t speak, but she remembers – isn’t that a perfect description of the weirwoods?

The other line of symbolism that plays into our line of research here is what happens with Stoneheart’s burning red eyes when she sees Oathkeeper:

He slid the sword from its scabbard and placed it in front of Lady Stoneheart. In the light from the firepit the red and black ripples in the blade almost seem to move, but the woman in grey had eyes only for the pommel: a golden lion’s head, with ruby eyes that shone like two red stars.

Cat has eyes only for the pommel – actually, she has eyes which are like the red stars eyes on the pommel, which are also a cat’s eyes, since the pommel is a lion head. It’s Dr. Seuss land again – a Cat with burning red eyes has eyes only for a cat with burning red eyes. Oathkeeper is a comet symbol, analogous to the catspaw figures and their Lightbringer-esque weapons, and Cat and the Brotherhood even name the sword and the bearer as a kind of catspaw of the Lannister King. Jack-Be-Lucky the one-eyed man says they should hang all three of them because “they’re lions,” Lem Lemoncloack says to Brienne that “there’s a stink of lion about you, lady,” and then they read the letter Brienne carries, which puts the nail in the coffin:

“There is this as well.” Thoros of Myr drew a parchment from his sleeve, and put it down next to the sword. “It bears the boy king’s seal and says the bearer is about his business.“

Lady Stoneheart set the sword aside to read the letter.

“The sword was given me for a good purpose,” said Brienne. “Ser Jaime swore an oath to Catelyn Stark . . .”

“. . . before his friends cut her throat for her, that must have been,” said the big man in the yellow cloak. “We all know about the Kingslayer and his oaths.”

That’s a nice one because in addition to naming Brienne and Oathkeeper as a catspaws of the Lannisters – “the bearer is about his business,” it doesn’t get any more catspaw than that – in addition to that, it also names the Freys who killed Cat as catspaws of the Lannisters, doing Jaime’s bidding. That means that both of Cat’s weirwood transformations were triggered by catspaws, by agents of the sun, which we interpret as the comet, and that lines up perfectly with all the weapons that attack Cat having Lightbringer symbolism. As I mentioned, Oathkeeper is also a great comet and cat’s paw symbol.

The point of the clever wordplay around Cat having eyes for and like the red stars on the lion pommel of Oathkeeper is the same as Melisandre having eyes like red stars, or Ghost having eyes like embers. It indicates a moon / weirwood symbol that has ingested the fire of the sun. Indeed, Oathkeeper’s ‘cat’ pommel and Catelyn-turned-Lady Stoneheart are parallel symbols. Oathkeeper’s lion pommel is the cat that has swallowed a red star, and the black and red blade would symbolize the comet that the lion swallowed. Longclaw, Jon’s sword, is just like Oathkeeper: the red-eyed wolf pommel is Ghost, who swallows Jon, and because Jon is a black brother and a sword in the darkness, Jon parallels to Longclaw’s black blade. It’s like the wolf pommel is swallowing the black sword and reflecting that internal fire in its eyes, just as with the red star-eyed lion pommel on Oathkeeper, and just as with Cat being attacked, throat slashed, and face-carved by Lightbringer symbols of various types, only to rise from the dead with burning red eyes.

Red Damascus Oathkeeper from Valyrian Steel – if someone will kindly donate one of these to the podcast before they run out, I’d be much obliged. Only $500! Name your own Patreon reward.

All of this symbolism is bolstered by Cat’s new name – Stoneheart. She has a stone in her heart, like a tree person that swallowed a stone – or like Oathkeeper’s lion pommel that swallowed a bloody dragon blade. Weirwood trees get set on fire by the dragon meteors and by the greenseers who play the role of meteors (the thunderbolt meteor, to be exact). Think of Bloodraven like the dragon Nidhog, sitting beneath the magical tree and animating it with his life fire. Bloodraven is like the meteor, like the stone which becomes the heart of the tree. So, the name Stoneheart implies a tree woman with a meteor stone heart, someone who swallowed a red star or red sun.

Weirwood: The Heart Tree fan art by wolverrain

We’ve also likened the King of Winter to a burning tree person – that’s essentially what he is, a wicker man made of dead greenery who is waiting to be burned in the spring. That obviously has overlap with the idea of Nissa Nissa becoming a burning tree, so what’s the deal with that? Well, it’s important to remember that gender doesn’t really exist with most trees and certainly not with moons and suns and comets – nor with dragons, for that matter. I talked about this last episode when I tried to explain that Nissa Nissa reborn and Azor Ahai reborn are really just gender appropriate versions of the same archetype.

For example, Cat has everything she needs to play King of Winter here except for a direwolf – she is sort of fiddling with Rob’s King of Winter crown, and now has Ned’s old sword too. And at the Red Wedding, Robb was actually acting in parallel to Cat: when he was first hit by an arrow, it says that he “staggered suddenly as a quarrel sprouted from his side,” which creates the image of a stag man growing wooden quarrels like tree limbs (hat-tip to my forum friend Unchained for that great observation). Cat thinks that if he screamed, she did not hear it because the music was too loud – making it a silent scream – and a second later, his voice is “whisper faint,” like a whispering weirwood (and remember that Robb won his most famous battle at the Whispering Wood).

Finally, we have Roose Bolton saying the infamous words “Jaime Lannister sends his regards” and then thrusting the longsword through Robb’s heart and twisting, making Robb and by extension the King of Winter some kind of Nissa Nissa moon figure. Like Nissa Nissa, and like the moon, the King of Winter parallels the tree, in other words – it’s a thing waiting to be set on fire. That’s also the case in real green man king of winter folklore: the king of winter is a green man made of dead garden shoots waiting to be set on fire at the changing of the season.

One other note on Roose stabbing Robb: by declaring himself to be a messenger of Jaime Lannister at the moment he stabs Robb, Roose is identifying himself as yet another catspaw assassin, and this creates another parallel between Robb as the King of Winter and Catelyn as a weirwood goddess, as both are killed by catspaws figures.

As kind of an adjunct to Catelyn, we’ll now return to the Inn of the Crossroads – also called the Gallows Inn – for a weirwood stigmata involving the death of the original owner, Masha Heddle. She is primarily mentioned in Catleyn’s chapters, so she fits in well here with all the Catelyn and lady Stoneheart stuff. Even though she is a minor character, her weirwood makeover scene unites much of the symbolism we’ve discussed here in the last three episodes. This from AGOT, when Tyrion meets his father there after coming down from the Mountains of the Moon:

The inn and its stables were much as he remembered, though little more than tumbled stones and blackened foundations remained where the rest of the village had stood. A gibbet had been erected in the yard, and the body that swung there was covered with ravens. At Tyrion’s approach they took to the air, squawking and flapping their black wings. He dismounted and glanced up at what remained of the corpse. The birds had eaten her lips and eyes and most of her cheeks, baring her stained red teeth in a hideous smile.

Masha Heddle is famous for her sourleaf-stained mouth, which is referred to many, many times in the first book. It’s called a “ghastly red smile,” a “hideous red smile,” and a “bloody horror,” so you get the idea. It’s a creative way of giving someone the weirwood bloody mouth symbolism, and it works quite well because of the vivid descriptions. Of course, the her red smile symbolism ties into the throat-cutting motif which is shared by the red smile of the weirwoods, and being hanged amounts to the same thing. Notice that the crows eating her face compare well to Catelyn’s fingernails being described as ten ravens when they disfigured her face, and of course to Bran’s eyes being pecked out by the Three-Eyed Crow. It’s also worth noting that she was hanged at the command of a solar king, Tywin, just as Cat was wounded and then killed by people doing the bidding of Lannisters. More catspaw symbolism, in other words.

Overall, what we can say about Masha Heddle is that she is the lady of the gallows inn, hung on the tree and given a weirwood transformation by the ravens and sourleaf: carved out bloody eyes, and a bloody smile. The blackened stone and ruined houses all around the inn and its gibbet help to lend the vibe of charred, smoking, ground-zero type wasteland. The gallows inn itself represents a weirwood as we saw in Garth of the Gallows, and the gibbet or gallows tree in the yard does the same. Of course we expect to see burning tree and weirwood symbolism at ground zero, so that all checks out and works in support of Masha’s weirwood transformation.

Now the configuration here is slightly different, because although her bloody eyes and red smile cast her in the role of the tree itself, usually it is Azor Ahai who is hung on the tree. This might suggest that perhaps Nissa Nissa was a woman who was sacrificed to open up the heart tree for Azor Ahai; perhaps she went in first and became part of the tree, only to have Azor Ahai then wed the tree and bond with it… or her, as it might be. Tywin, a solar character, hanged Masha Heddle and then takes up temporary residence in her inn, which kind of fits that pattern, so we’ll keep this possibility in mind. Tyrion is an Azor Ahai reborn figure, and he comes down the Mountains of the Moon (like a moon meteor) and also enters the weirwood symbol of the gallows inn, passing by the hanged and weirwooded Masha Heddle.

There’s one other honorable mention weirwood maiden that belongs with Cat, and that is Brienne, who I said is like a moon character that turns into an Evenstar Morningstar character. The Venus of Tarth, Brienne the Beauty. We talked about her hanging on the tree in Garth of the Gallows, and about how she is repeatedly struck by lightning, so to speak, in various scenes. After she has the horrific fight with Rorge and then Biter, she is patched up a bit by the Brotherhood without banners and taken to Lady Stoneheart, and for a time, she floats in a world of hazy half-dream. One of those dreams is worth a quick mention here. It’s the one where she dreams of the time that Red Ronnet Connington, he of the fire-red hair and beard, came to Evenfall hall to officially court her – except in the dream, Ronnet becomes Jaime part-way through.

The main noteworthy thing is that when Ronnet / Jaime gives her the rose, she opens her mouth and blood pours out – “she had bitten off her tongue while she waited.” A rose from a sun character would be a stand-in for the comet, and to confirm this, we get the following lines from Brienne on a different occasion when she recalls facing Red Ronnet on the tourney ground and exacting her revenge for his ‘courtship,’ and the cruel prank he participated in with the other knights:

In the mêlée at Bitterbridge she had sought out her suitors and battered them one by one, Farrow and Ambrose and Bushy, Mark Mullendore and Raymond Nayland and Will the Stork. She had ridden over Harry Sawyer and broken Robin Potter’s helm, giving him a nasty scar. And when the last of them had fallen, the Mother had delivered Connington to her. This time Ser Ronnet held a sword and not a rose. Every blow she dealt him was sweeter than a kiss.

It’s the kissing and killing, sex and swordplay theme between these two, and the rose is now a sword. Then during Brienne’s hazy half-conscious nightmare dream on the way to Stoneheart’s lair, we get this:

“He will bring a rose for you,” her father promised her, but a rose was no good, a rose could not keep her safe. It was a sword she wanted. Oathkeeper. I have to find the girl. I have to find his honor.

In other words, Oathkeeper is be likened to the rose – and indeed, it was Jaime who gave her Oathkeeper, just as he gave her the rose in the dream. The sun gives his fire to the moon maiden, which means that Brienne must be playing the moon maiden in this dream, at least. Brienne having revenge on Red Ronnet would equate to the moon meteors killing the sun with meteor smoke – the lunar revenge motif – and the same is true when she battles Jaime, a scene we will break down another time. Earlier in AFFC, Brienne dreams of her revenge on Red Ronnet, and we see that Jaime and Ronnet share another familiar symbol:

Ronnet had a rose between his fingers. When he held it out to her, she cut his hand off.

The last detail has to do with Brienne’s dress, made out like the sigil of House Tarth: “a quartered gown of blue and red decorated with golden suns and silver crescent moons.” It’s pretty great ice and fire unity symbolism, and more importantly, sun and moon unity symbolism. The merging of sun and moon is what converts Brienne from moon maiden to falling Evenstar, after all. And finally, and this will be a preview of the next episode, Brienne has her second-hand shield painted to look like that of her ancestor, Ser Duncan the Tall: a falling green star and an elm tree on a field of sunset. That’s basically a diagram of the thunderbolt meteor about to strike the tree, and right at sunset (when the sun is swallowed by the trees).

Alright, so that’s our first batch, with Lady Catelyn and Masha Heddle being vivid and precise depictions of women turning into weirwoods, and Brienne being a less complete echo with only the bloody mouth – although she is hanged, rhetorically struck by lightning several times, and given a sword with Lightbringer symbolism. We will also catch Brienne in another scene later on.

Antler-Eater

This section is brought to you by Ser Imriel of Heavenly House Orion, spinner of the great wheel, formerly of House Jordayne of the Tor and now the earthly avatar of the Sword of the Morning

Up next we have Melisandre of Asshai, whom we have talked about a fair amount in the last episode and in previous episodes. She’s well-established as a Nissa Nissa fiery moon maiden figure, and we will come across those familiar symbols even as we primarily focus on the way that Melisandre plays into the idea of Nissa Nissa representing a weirwood. Just as with Catleyn, the moon maiden and weirwood maiden symbolism will appear side-by-side and intertwined with one another.

Melisandre actually starts off looking the most like a weirwood of all the moon maidens – she has skin as pale as cream, while everything else is red. Of course she has that red hair that is like blood and flame, which is comparable to Cat, Sansa, Ygritte, and a few others, but she also has the red eyes to better match a weirwood. She also wears red robes that are meant to look like shifting flame, with some layers looking like blood instead, so in basically every sense, she already looks like she is perpetually bleeding and burning, like the weirwood.

Here’s a good example, from the beginning of the burning of the seven scene in ACOK:

Melisandre was robed all in scarlet satin and blood velvet, her eyes as red as the great ruby that glistened at her throat as if it too were afire.

The weirwood blood sap that crusts their eyes and mouth can look like ruby as well, as we see in a line from AGOT that takes place inside the weirwood grove of nine:

The wide smooth trunks were bone pale, and nine faces stared inward. The dried sap that crusted in the eyes was red and hard as ruby.

In ADWD, Mel’s ruby was called “a third eye glowing brighter than the others.” This is directly suggestive of third eye vision, a la Odin and the greenseers – in fact, the third eye phrase is used seven times in the series proper, and all of them refer to Bran’s greenseer abilities, except this one here with Mel’s ruby. This is why the weirwood having ruby eyes is such great symbolism – it implies a link or similarity between Mel’s ruby third eye vision and the ruby eyes through which a greenseer looks when he opens his metaphorical third eye. Please remember, I am not suggesting that Melisandre is necessarily a greenseer, though that is not impossible if she is the daughter of Bloodraven and Shiera Seastar, as Radio Westeros theorizes. The point is that Melisandre is symbolizing the archetypal burning weirwood which Azor Ahai entered.

Melisandre burns a weirwood tree

by kika8717 on DevianArt

That leads to our next point: Melisandre shows the signs of having swallowed the red fire of the sun. In the last episode, we discussed how Mel’s eyes like red stars and Ghost’s eyes like embers both allude to the concept of moons and weirwoods swallowing the fire of Azor Ahai, and today we’ve roped Lady Stoneheart and her burning eyes like red pits into this symbolism (get it… roped… it’s a hanging joke. Call it gallows humor.) Melisandre’s red eyes are also described as candles and torches, which is more of the same, as well as hot coals, which matches the description of Drogon’s eyes right after he is born in the pyre of Khal Drogo .

You’ll recall her famous lines from her fire vision in ADWD: “Blood trickled down her thigh, black and smoking. The fire was inside her, an agony, an ecstasy, filling her, searing her, transforming her.” She also weeps, and it says “her tears were flame.” This is great weirwood portrait stuff – the weirwood is a picture of a bloody and burning moon, and Melisandre is having her blood burned and seared by some kind of magical fire, which has gotten inside her. The same thing happened to Dany at the alchemical wedding when she had the fire inside her, and like Dany, Mel is clearly playing the Nissa Nissa role here, with the ‘agony and ecstasy’ being a clear callout to the original moon maiden.

She’s definitely got the fire inside her, it’s safe to say, just like Dany. We see this not only in her eyes, but in the fact that she is, well, shagging a dude with a flaming red sword whom she thinks is Azor Ahai reborn. Melisandre speaks often of having red R’hllor’s fire inside her as well, and R’hllor is a god, so that is quite specifically the fire of the gods which Mel has swallowed. She is therefore a wonderful match to the trees and wolves that swallow the dying sun fire. That’s a description of Stannis if I ever heard one – he’s a solar king, kinda, but really he’s a solar king who is being overtaken by shadow and who is turning into the dark solar king, the dying sun fire. That’s an archetype which overlaps with the Night’s King, whom Stannis shows signs of paralleling.

Stannis Baratheon Sigil Poster

by P3RF3KT on DeviantArt